On This Date In History

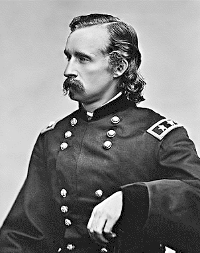

Custer, Selfishness, And The Little Bighorn

September 17, 2015

Introduction

If the Battle of the Little Bighorn accomplished anything it did one thing for certain: it produced questions. Participants, researchers, and authors have weighed in on these questions over time but there has often been little agreement in their answers.

There is one question though that almost always receives the same answer. The question:

Was Custer selfish leading up to and during his final battle?

The answer from many is a resounding "yes", and some believe it is one of the main reasons why he lost.

The Trouble With Proving Selfishness

The trouble with proving selfishness is that unless the person held in suspicion of it acknowledges it, proving it can be difficult. It can be difficult to prove because selfishness is a motivation, it is internal. Without a clear acknowledgment of a motivation, the person looking to prove it must use a person's words and actions to look into their very heart and mind. This of course can be a very difficult task and the result is often a guess or interpretation, not a proof.

The Trouble With Proving Selfishness In Custer

In Custer's case in particular, there is no clear acknowledgment by him that he was selfish leading up to or during his final conflict. This leaves those who maintain that he was in a difficult position. The only thing left is to interpret their words and actions.

One Selfish Proof

One proof some may offer that Custer was selfish leading up to the Little Bighorn is that he seemed to acknowledge such in a letter to his wife.

On June 21st, 1876 (four days from the Little Bighorn Battle) Custer wrote:

"The scouting-party has returned. They saw the trail and deserted camp of a village of three hundred and eighty (380) lodges. The trail was about one week old. The scouts reported that they could have overtaken the village in one day and a half. I am now going to take up the trail where the scouting-party turned back. I fear their failure to follow up the Indians has imperilled our plans by giving the village an intimation of our presence. Think of the valuable time lost! But I feel hopeful of accomplishing great results. I will move directly up the valley of the Rosebud ..."1

Custer's critics may say: "See? He desired "great results", those words prove that he was selfish and interested in winning a victory for his own good - so he could win acclaim, etc...."

The First Problem With The Proof

The first problem with that proof is that Custer does not say that he wanted the great results for himself. He doesn't even say why he wanted great results. This is not an acknowledgment of selfishiness. Any conclusions drawn from this statement about why he wanted "great results" are interpretations.

The Second Problem With The Proof

The second problem with that proof is that less than a year before Custer wrote to his wife about "great results" he wrote another letter and used that very same phrase - but not in regards to himself or his efforts. I've taken the liberty of emboldening the phrase in the letter below.

On September 17, 1875 Custer wrote to a Dr. Newman about a religious worker who had been ministering to his men.

"... He has impressed all with whom he has been associated with his unselfishness, his honesty of purpose, and his great desire to do good.

It is but due to him and the holy cause he represents, and a pleasure to me, to testify to the success which has crowned his labors, particularly among the soldiers of this command. If our large posts on the remote frontier, which are situated far from church and Church influences, had chaplains who were as faithful Christians as I believe Mr. Matchett to be, and who, like him, are willing to labor faithfully among the enlisted men, the moral standard, now necessarily so low among that neglected class, would be elevated far above its present level, and great results would follow."2

This letter demonstrates conclusively that Custer's use of the term "great results" should not automatically be seen as a selfish phrase, for here he's not even referring to himself or his work. Actually, he uses the phrase in connection with a cause and efforts that could be seen as being the opposite of selfish. Further, in the letter he communicates his concern for the welfare of others.

Also, in describing the minister, he uses the word "unselfishness" - and later states that if there were more like him "great results" would follow - further strengthening the case that Custer's use of the phrase does not automatically mean selfishness. Indeed, it could be said with confidence that Custer was claiming that unselfishness could work toward the accomplishment of "great results".

Conclusion

Proving selfishness in anyone is almost an impossible task without an acknowledgment of it from the party held in suspicion - anything else is interpretations and guessing.

While some may claim that Custer's use of the phrase "great results" prior to his final battle means he was selfish, such an interpretation would be inaccurate.

- First, Custer does not state why he desired "great results".

- Second, he used the same phrase less than a year before in regards to an effort that could be seen as being the opposite of selfish.

- In the letter where he used the phrase a year before, he actually made a connection between unselfishness and the potential for "great results".

These three points ought to demonstrate conclusively that this proof of Custer's selfishness is invalid and that his use of the phrase "great results" does not automatically mean he was selfish. This misinterpretation could still do do some good though. It could serve as an excellent example of how misinterpretations can tarnish the reputation of any historical person.

Sources:

1. Custer, Elizabeth Bacon. "Boots and Saddles"; Or, Life in Dakota with General Custer. New York: Harper & Bros., 1885. 311-12. Print.

2. Custer, Elizabeth Bacon. "Boots and Saddles"; Or, Life in Dakota with General Custer. New York: Harper & Bros., 1885. 249. Print.

About the Author

Tim Kloos is an online advertising professional. He helps clients with their websites, online presence, and online advertising. If you need help with any of these, feel free to contact him via the contact page.

His tech website is clevelandwebdesignplus.com.

He has also written a children's book set in the Old West.